My approach to bow making

- In the first place I try to find original bows that are in the possession of musicians. This gives me the considerable advantage of being able to try out the bows in order to gain an impression of their playing characteristics.

- Sometimes I measure and photograph bows in museums; however, such bows are mostly not in playable condition so I cannot experience how the bow actually plays.

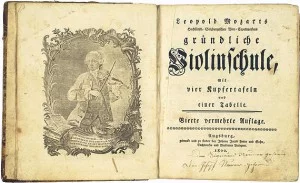

- On rare occasions I use a painting as my inspirational basis, if there are no surviving original bows to serve as a model. This is the case with the Marais gamba bow.

Historical bow-making techniques

Historical aspects

It is important to know how the instruments of the period sounded, how they were strung and their specific tuning pitch. I have acquired much of this knowledge from my studies and experience as a Baroque violinist.

‘In their letters, W.A. Mozart and his father wrote that they preferred a strong, clear “masculine” tone, with much shading, individuality, feeling and “taste”. Wolfgang described Tartini’s style as expressive, but rather thin sounding. Tartini’s two surviving bows are extraordinarily light, one a long Baroque model and the other a high-tip example, both with clip-in frog. Tartini speaks of playing primarily in the middle of the bow.’ (Excerpt taken from an article by the bow maker Stephen Marvin in The Strad, 2006)

It is essential to interpret these notions guided by our knowledge of the musicians’ customary practices typical of that period and place.

Choice of wood type